TITLE: Mga Lumadnong Sugilanon nga Mahinuklogon

AUTHOR: Melchor M. Morante

Published by Aletheia Printing and Publishing House, Davao City

Virtual book launch on 30 December 2020 at 4 p.m.

KIDAPAWAN CITY (MindaNews / 16 December) — A genre of its own emerges from Melchor M. Morante’s latest book Mga Lumadnong Sugilanon nga Mahinuklogon, a collection of short stories in Cebuano Bisaya.

Written by an author with decades of experience working with Mindanao’s marginalized communities, these roman-a-clef stories are to date the largest collection of works of what I will hitherto call Historical Injustice Fiction.

These stories – and the literature they end up becoming – are now welcome additions to Mindanao’s collective memory, serving to help address many of this island’s many historical injustices: Landgrabbing, historical and cultural erasure, extrajudicial killings, socioeconomic inequality, and linguistic hegemony all touched in stories casually told as reflective recollections.

Using fiction as a means of documenting and bringing historical injustices into wider public awareness is not new, but with Mga Lumadnong Sugilanon nga Mahinuklogon, a new direction is emerging: specific incidents of atrocities or injustices in Mindanao, specially those not widely known or remaining unrecorded, are portrayed and tackled with the sobriety of literary detachment, such that human insight may be distilled from them, specially for Mindanawon readers.

As I have said in different occasions, the culmination of literary form is impact, and in order to achieve that impact, that form must be scrutinized. Taking at look at how Morante’s stories succeed, and see where they can improve, would also serve to take this emerging genre forward.

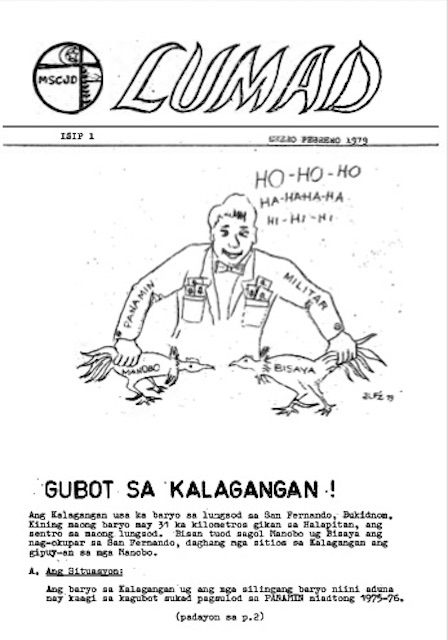

We note, first of all, the language, and with just this the stories in this collection already have much impact.

For the longest time, Mindanao’s Fiction in Cebuano Bisaya has been largely monolingual, a result of Bhabhan hybridity of Mindanao’s writers from the ‘standard’ Cebu tradition of the language’s literature, but also a cause by which Mindanao’s own tradition remains so, producing this endless cycle of uprootedness. This is an often ignored dimension to the reality of contemporary Mindanao literature’s longstanding failure to reflect Mindanao’s linguistic realities. With the more recent works of writers like Jondy Arpilleda (who blurs the lines between Bisaya and Tandagnon) and Macario Tiu (who proudly uses the Tagalog-laced Bisaya of Davao), this remove between literary medium and linguistic reality is slowly being addressed

But Mga Lumadnong Sugilanon nga Mahinuklogon takes this one step further, with the author making it his express aim in the collection’s introduction to show more of Cebuano Bisaya’s increasing hybridization with other languages in Mindanao. With Tagalog, English, and Hiligaynon mixing with Monuvu, Blaan, Subanen, and Dulangan in the Cebuano narrative, this collection’s medium is, to date, the closest any book has come to what Mindanao actually sounds like.

But Mga Lumadnong Sugilanon nga Mahinuklogon takes this one step further, with the author making it his express aim in the collection’s introduction to show more of Cebuano Bisaya’s increasing hybridization with other languages in Mindanao. With Tagalog, English, and Hiligaynon mixing with Monuvu, Blaan, Subanen, and Dulangan in the Cebuano narrative, this collection’s medium is, to date, the closest any book has come to what Mindanao actually sounds like.

We want more of course, and in many accounts that demand is addressed not to the text, but to the community. Mindanao’s indigenous languages (this collection shows) is not being heard enough in Mindanao, a result of their slow erasure in the wake of policies of linguistic hegemony (the premium put on English, the imposition of Tagalog as a national language, and the emergence of Cebuano as Settler lingua franca resulting from unmediated resettlement). Morante’s stories also succeed by showing how Mindanao’s languages have become subaltern even in Mindanao. We are compelled to do something about it.

Where, perhaps, the collection can improve on the matter of language is with the following of emerging standards of orthography and in being representative of the picture of diversity.

I cannot speak for the other Lumad languages, but for Obo Monuvu (which I am learning), I can point out that it would be ideal if the author follow the orthography for the language developed by tribal leaders in partnership with the Summer Institute of Linguistics. Greetings such as ‘moppiyon sollom’ (which are used in the stories) are increasingly being spelled by the language’s writers following this orthography, which the tribe themselves designed to better reflect their phonology.

The discourse on what orthography to follow is also deeply intertwined with discursive power, and it would be consistent with this collection’s aim – and for Historical Injustice Fiction in general – to spell words in the language the way the language community itself would like them to be spelled.

Although it is not really the problem of the collection (which is already considerably diverse), it must also be pointed out that the book is still far from representing the sheer multiplicity of tongues in Mindanao, one of the world’s linguistic diversity hotspots. Not featured in the book are the Moro languages, many Lumad languages, and Settler languages endemic to Mindanao like Chavacano and the Mindanao Tagalogs. But that only means that we hope more works will come out featuring those languages’ confluence with Bisaya.

In terms of form, the stories in the collection often fall short of narrative development. Each story is rich in ethnographical and historical material, with much of those having their own conflicts. But the stories suffer from overreliance on them, and perhaps the author’s own general sense of detachment from the events unfolding. Although it must be quickly pointed out that the author is in no way apathetic, on the contrary there is much sympathy for the conflicts unfolding in each piece from the narrator. Only that it seems that the narrator is too often merely the bystander, and being another level removed from the human experience, the reader can only really eavesdrop into what that bystander is hearing.

The emotional gravity of such situations as the death of the grandson in ‘Lakewood’ and the evacuations recounted in ‘Buklog’ do not come out, in the first case because the narrator (and consequently the reader) has not been shown to have developed any deeper attachment to the dead child, and in the latter case because the reader is not given the opportunity to be in the narrative present of the incident being recounted.

The same is true of the character development of the eponymous ‘Kampo,’ whose change of personality the reader (like the narrator) can only speculate about but do not really full experience.

Balancing the volume of historical and ethnographic material to discuss on the one hand and creating a human conflict at the heart of the story on the other will be a central and recurring challenge to any future writer of Historical Injustice Fiction.

Where I think writers like Morante can move forward on that count is to find a conflict through which the author can add their take on the discourse of the subject matter, the insight they draw from the issue, or perhaps their idea how it could be resolved.

The wealth of material to discuss also makes it very tempting for the writer of Historical Injustice Fiction to dump information that, while of great interest, may be unnecessary to the story and may in fact drag the story down and lose the reader’s interest. This the case in ‘Kampo,’ where the discussions on the religious characters’ work gets more attention than Kampo’s own sudden change in personality.

The introduction of the collection gives full disclosure that the stories are all Roman a Clef, with the names of characters and places changed to respect the privacies of people. But the author is actually inconsistent on this account, as in some stories he renames entire towns (‘Malpet’ for ‘Magpet’ in North Cotabato in ‘Natik Ansaban’ to name one) but in others he even uses the town’s real name, (‘Lakewood,’ for instance).

Altering the names would, I think, only cause unnecessary frustration, specially as many of the incidents being described are in fact publicly verifiable.

The subject of the first story in the collection, ‘Natik Ansaban,’ was particularly easy to identify, specially for a reader like me doing research into Kidapawan history. The Katindu Dispute, which started in the 1960s and was only resolved in the 1990s, involved the Monuvu Ansabu clan, lead by Datu Amasing and Datu Mambiling Ansabu, and the land-grabber Augusto Gana, who became mayor of Kidapawan from 1971 to 1992 (in the story his caricature, Hulyo Alegre, became governor, but in real life his wife Mila Ocampo Gana became a provincial board member, and together they were influential in the province).

‘Satur Neri’ is inspired by the martyred priest Fr Nery Lito Satur, who fought a long crusade against logging in Bukidnon. The displacement of the Subanen resulting from the insurgency in Mt Malindang portrayed in ‘Buklog,’ as well as the exploitation of the burial jars in Sultan Kudarat are all well documented.

But the others whose real details I and other readers are not privy to only cause frustration, as there is a desire built up to learn more about these real incidents, specially considering the author – who has spent decades working with communities – offers a historically important perspective never before heard. This was particularly the case with ‘Kampo,’ whose real location I could not ascertain.

I find that changing the names, specially of places and public figures, would be counterproductive to the project of raising awareness about historical injustices, as for such an endeavor you want to be as informative as you can for all of posterity. There is a sense in this collection that the author understood this in many of the stories, which did not really hide any names.

Outside of form, writers who would attempt to write works of Historical Injustice Fiction must be conscious of the complexities of discourse in Mindanao, and the dynamics of representation and the subaltern.

Which is why there is a need to properly translate this book’s title to English.

‘Lumadnong Sugilanon’ would be simply translated to ‘Lumad Stories’ by less aware editors. But such a translation would create the false impression that these stories are by the Lumad and articulate Lumad worldviews. This, for the Settler author, would be tantamount to Settlerjacking .

This danger is especially true if these stories were handled by anthology editors and literature teachers without nuance (and there are many), and it would only add to the pervading problem of cultural misrepresentation if this collection were not curated properly.

And proper curation is what this collection deserves, as they are very insightful stories about the Lumad (a much better translation of the title!), ones told from a very empowering perspective.

Mga Lumadnong Sugilanon nga Mahinuklogon is a triumph of Settler fiction, because few Settler stories ever portray the Lumad with the same level of respect, admiration, and empathy as much as these stories do. In these stories you see most of all that the Lumad are people, with very human struggles that any reader can relate to.

Even the ignorance of the Lumad is cause for the Settler’s respectful amusement. In ‘Kampo,’ the narrator shares the eponymous Dulangan Manobo character’s excitement to see the sea (which he had never seen up close before). When Kampo wonders if he can use sea water to cook Sinigang, the narrator delights at this fresh way of looking at something he had always taken for granted. Charming moments like these remind us, both of our shared humanity and the many differences we can celebrate.

What make these stories particularly special is how much it reveals – and exemplifies – about the Settler perspective. The narrator is conscious of his Settlerhood, and has the wisdom to be wary of the perils of projecting his own aspirations on the communities he is working with. In these stories, most of the talking actually comes from the perspective of the Lumad characters (either as dialogue or as recounted by the narrator), and the narrator rarely adds his own perspective into the details. The author being a seasoned community worker, this comes as no surprise. And this is an attitude every Settler, specially the well meaning ones who will endeavour to take up the challenge of writing Historical Injustice Fiction, will need to assume.

It is of course de rigueur for anyone writing about cultural communities to be judicious in the ethnography they depict, because fiction has a way of distorting public understanding of anthropology. This is especially true for works of Historical Injustice Fiction, as cultural distortions are themselves acts of historical injustice (an injustice I think such fictionists as Erwin Cabucos, Jude Ortega, and the late Antonio Enriquez were often guilty of). The author behind the nom de plume Melchor M. Morante is a seasoned anthropologist, so that rarely poses a problem for this collection.

The Settler author is also rightly candid about the devastating effects of Settlerhood and the poor environmental and economic policies of the colonial Philippine nation-state imagined from Manila on the indigenous cultures of Mindanao. In one story, poorly thought out land titling policies are shown to have led to landgrabbing. In another, the coming of public health institutions are shown to be killing ancient healing traditions (very timely as the national government is now considering recognizing indigenous healers as Preservers of Intangible Cultural Heritage). And yet in another, the Manila-centric and Urban-centric nature of cultural institutions are shown to be the cause of looting of historical and archaeological artefacts.

One of the most poignant scenes in the whole collection is in the story ‘Lakewood,’ when the Manilenya nun casually makes a feminist commentary on the Subanen legend being recounted. Not only is this a demonstration of typical Manilenyo naivety and unwitting cultural imposition, the narrator’s response – that cultures are to be respected if they are to be understood – is wisdom every Mindanawon should aspire to.

But particularly fascinating is how, in these stories, the author offers a glimpse into Mindanawon Catholic attitudes towards the Lumad and their indigenous spirituality. The early days of Christianity in Lumad Mindanao were characterized by coerced conversions and systematic discrimination. In this collection, we see how the Catholic church and its institutions have actually taken a complete u-turn in dealing with indigenous spirituality, one for the better. Instead of dismissing the Lumad spiritual traditions as ‘paganism’ or ‘witchcraft,’ there is often an awed fascination on the part of the narrator, a member of a religious order. This already goes beyond mere tolerance, the author is showing how Mindanao’s Christian Settlers (specially its more mature Catholics) are starting to celebrate the many ways of being human and aspiring towards the Infinite here in Mindanao. This collection, I think, argues quite eloquently how Mindanao should be developed as an important center for theology.

Just the last word in the book’s title, Mahinuklogon, opens up so many possibilities. ‘Paghinuklog’ is conventionally translated to ‘contemplation,’ with a note of ‘repentance,’ and in Settler Bisaya is a term invariably belonging to the semantic field of Kwaresma (the Lenten Season), in other words of religious reflection. And yet it is tantalizingly similar to the Subanen ritual of the Buklog (the title of one of the collection’s stories), and if not a cognate, is certainly evocative of that grand indigenous ceremony. By just that one word, the book’s title serves to subtly remind Mindanawons how much we actually share with one another despite our ethnic and religious differences, and how much we would discover if we only overcame prejudices and try to understand one another.

Mga Lumadnong Sugilanon nga Mahinuklogon is the first literary book to come out from Mindanao since the coming of the global Coronavirus Pandemic (part of the ongoing Cultural boom in Mindanao).

And rightly so: in a time when we are dealing with many deaths and compelled to stay at home to read and reflect, literature that is lived – like these works of Historical Injustice Fiction – becomes more relevant.

Because when you talk about historical injustice, you cannot help but usher in the coming of healing.

(MindaViews is the opinion section of MindaNews. Karlo Antonio Galay David documented five previously unrecorded civilian massacres, the obscure lives of many local historical figures, and the details of dozens of forgotten historical incidents in his hometown of Kidapawan City, North Cotabato, where he is currently working as local historian for the City Government. He has a Masters in Creative Writing from Silliman University, and has won the Don Carlos Palanca and Nick Joaquin Literary Awards. He has seen print in Mindanao, Cebu, Dumaguete, Manila, Hong Kong, and Bangkok)

Weaving this documentary entailed time and risks for its directors Jean Claire Dy and Manuel Domes from Germany. But both directors share a common purpose of focusing on narratives to draw out peoples’ tales on conflict and peace. These tales will make viewers see Marawi as broken pieces that may take years or decades to be put together.

Weaving this documentary entailed time and risks for its directors Jean Claire Dy and Manuel Domes from Germany. But both directors share a common purpose of focusing on narratives to draw out peoples’ tales on conflict and peace. These tales will make viewers see Marawi as broken pieces that may take years or decades to be put together. The film was originally set for release at Sinag Maynila 2020 but was postponed due to the pandemic. It was shown at the Pista ng Pelikulang Pilipino in October 2020 which garnered Best Supporting Actor award for Henyo Ehem and Best Sound Design for Barbarona.

The film was originally set for release at Sinag Maynila 2020 but was postponed due to the pandemic. It was shown at the Pista ng Pelikulang Pilipino in October 2020 which garnered Best Supporting Actor award for Henyo Ehem and Best Sound Design for Barbarona. MALAYBALAY CITY (MindaNews / 02 September) – Back in 2005, the nongovernment organization I used to work with assisted the Bukidnon-Daraghuyan tribe in Malaybalay City in the processing of their application for a Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT). As it went along, I realized that applying for a CADT is a tedious, costly process, which gave me the impression that it has become another form of oppression for Lumads (indigenous peoples of Mindanao) who don’t have the resources for it.

MALAYBALAY CITY (MindaNews / 02 September) – Back in 2005, the nongovernment organization I used to work with assisted the Bukidnon-Daraghuyan tribe in Malaybalay City in the processing of their application for a Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT). As it went along, I realized that applying for a CADT is a tedious, costly process, which gave me the impression that it has become another form of oppression for Lumads (indigenous peoples of Mindanao) who don’t have the resources for it.